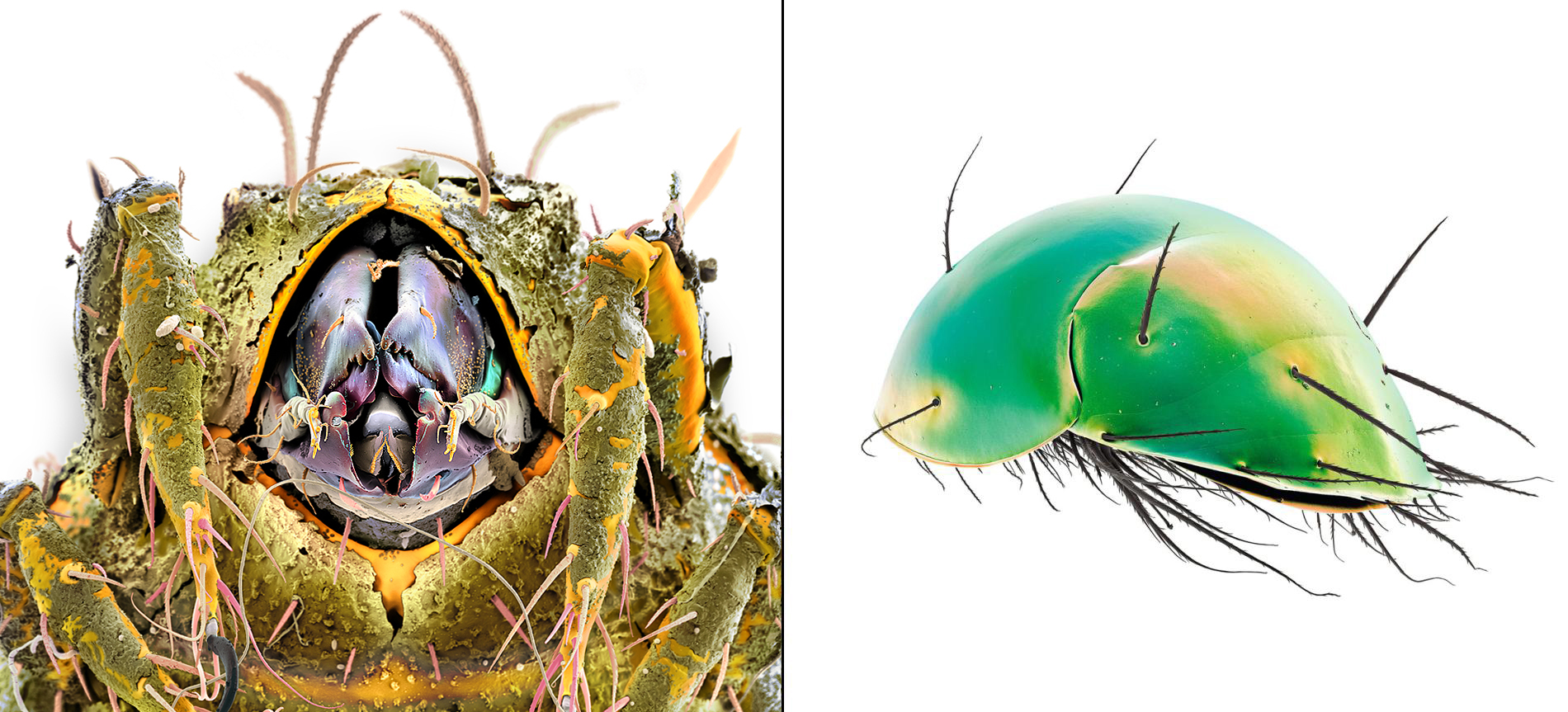

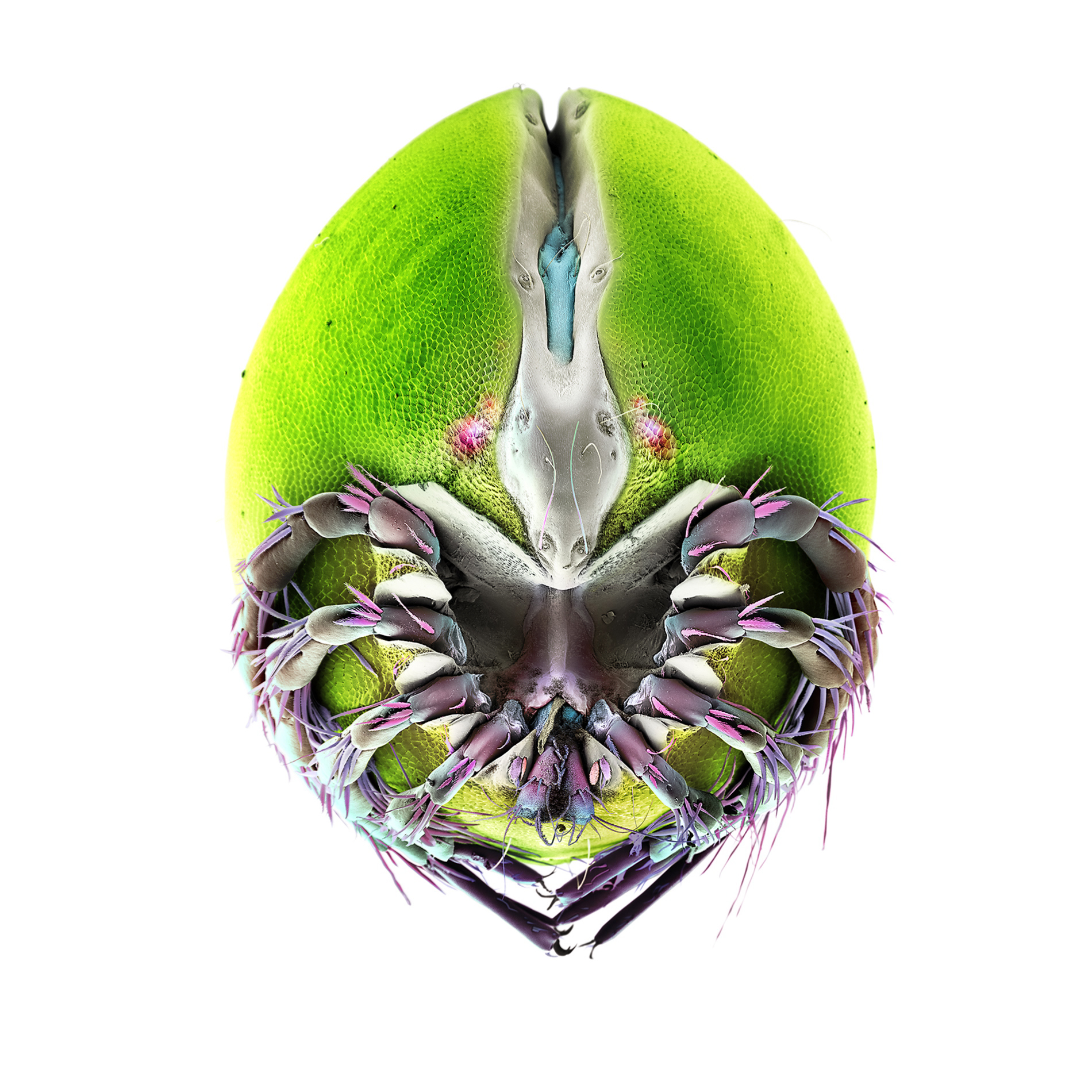

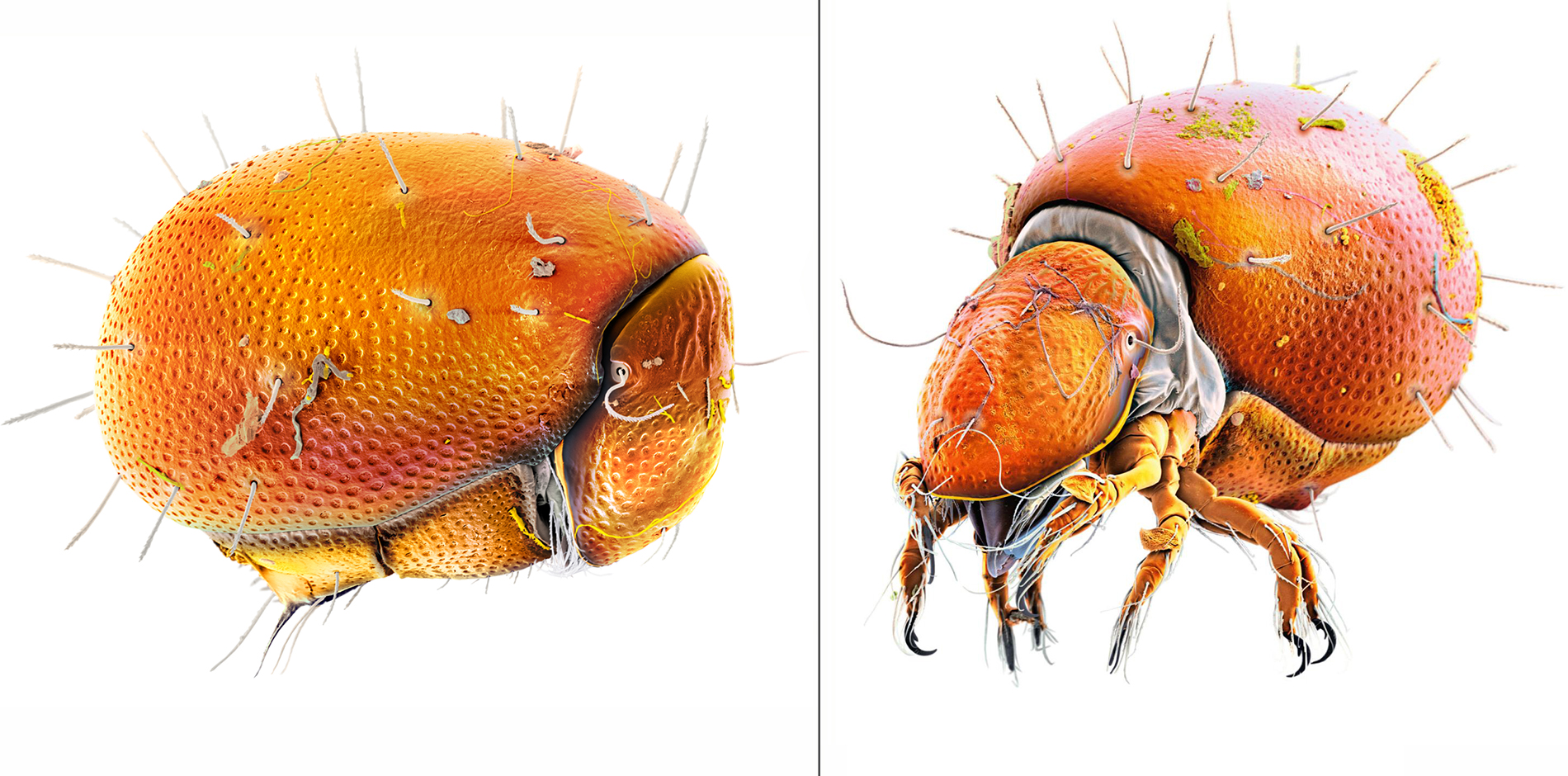

Images produced with the ScanninG-Electron-microscope (SEM)

Oribatid soil mite (left) and a scutacarid mite (right).

Martin Oeggerli aka Micronaut sees the world as scientist and artist: both perspectives are reflected in his pictures which are based on scanning-electron-microscopy (SEM) and manual post-processing (‹coloration›). Utilizing electrons instead of photons allows to find and explore invisibly small creatures and materials, often with magnifications up to 100’000-times or more. By combining hi-tech SEM with his signature-style coloration, Micronaut exposes surreal looking motives down to the smallest details and thereby expands the limits of traditional photography.

“The images are utterly sensational! The clarity and colors are gorgeous… truly one of a kind images.”

Navigating Between Art+Science

Text by Todd James

Published by National Geographic, 2015 (‹Dr. Oeggerli’s beautiful little monsters‹)

Some people find Dr. Martin Oeggerli’s monsters a little frightening. I see beauty in them, perfectly shaped by evolution. I also see a hint of Charles Darwin and Albrecht Dürer: the scientist and the artist.

This image of a soil mite (Parazercon) magnified 556 times, took 59 hours to color.

Mites don’t have a particularly nice reputation, but how well do we really know them? Oeggerli wants to help us to see past our preconceptions and beyond the limits of our own eyes. With a scanning electron microscope (SEM), he explores the microcosmos—the tiny, unseen world that’s smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. There he finds exotic creatures with endless forms of evolutionary specialization. These creatures are perfectly adapted to their environment, by their environment.

When Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859 he was not writing for an elite group of scientists. He was speaking to the rest of us. Darwin challenged the public to see and understand the natural world in a wholly new way.

Frontipoda is a predatory mite that lives in small ponds and feeds on larval midges.

Oeggerli, who studied zoology and has a Ph.D. in cancer research, seems to be following Darwin’s lead by exploring the biodiversity of the invisibly small world and inviting us along on his journey.

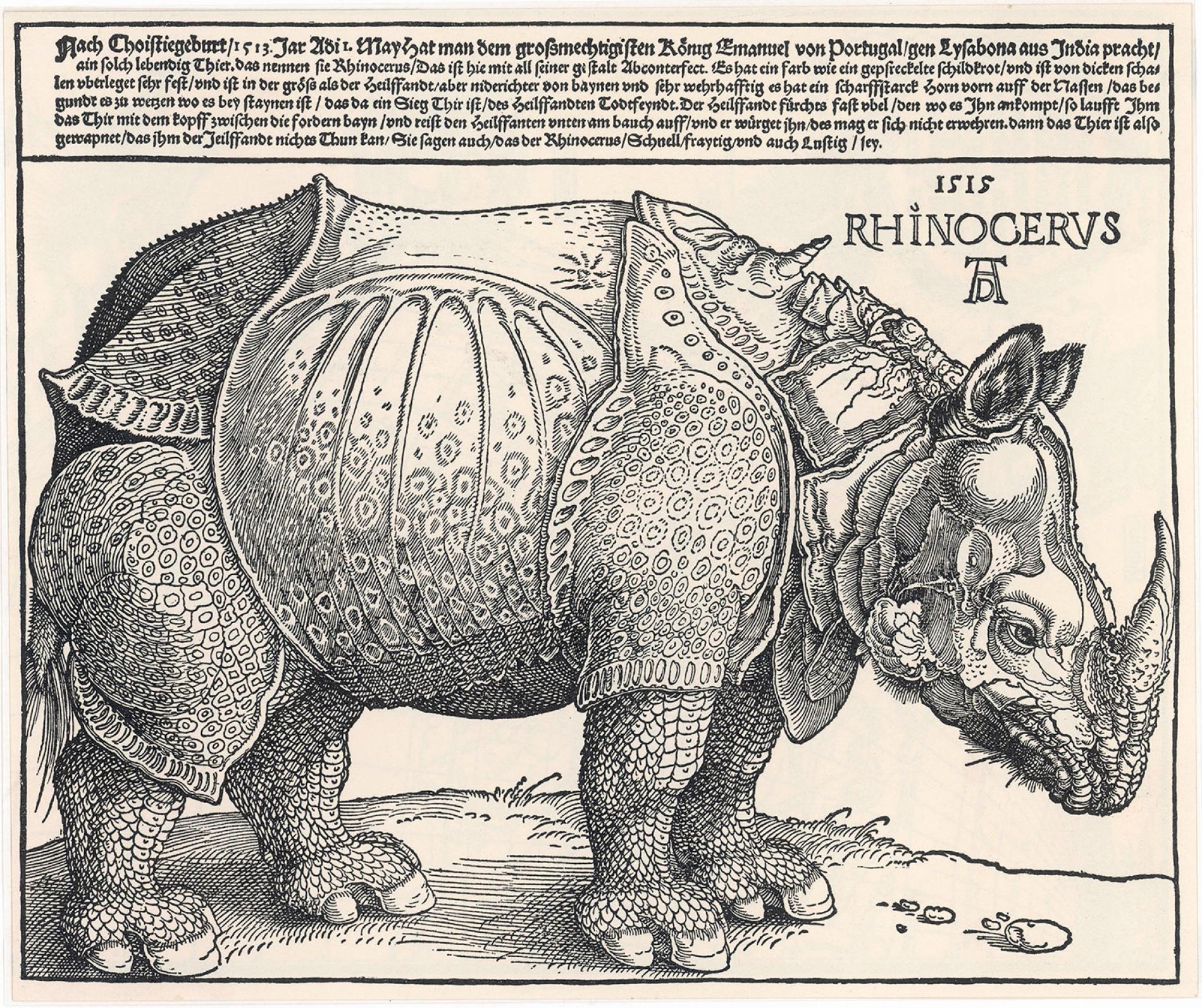

His work also reminds me of Dürer’s rhinoceros. This strange creature, unknown to Europe in 1515, captured the imagination of the entire continent partly because the artist’s famous etching made it visible. Whatever his work of artistic interpretation lacked in accuracy, it made up for with its sheer beauty, its strangeness, and its power to inspire the imagination. Dürer was an artist drawn toward science, or at least animated by its principal ingredient: curiosity. Oeggerli is a man of science drawn toward artistic interpretation: Art multiplies science for him.

Mites of the genus Schwiebea are found in many places, from soil and tree cavities to mushrooms, decaying wood, and swimming pools.

Albrecht Dürer’s Indian rhinoceros, depicted in the year 1515. Mary Evans Picture Library

Image source: Wikipedia

technology: So how does he do it?

Oeggerli’s photographs can take several months to create. In fact, the completion of a series of images may stretch from half a year up to a decade.

To obtain exquisite specimens, that are in perfect condition, Oeggerli works closely with research scientists. Each sample has to be carefully dried using special solvents to maintain its natural shape and appearance. After this the sample is also coated with a thin layer of gold, to make it electronically conductive. It’s one of several critical steps during the conservational process which will finally affect the image quality and maximum printable size of every resultant picture.

Utilizing a Scanning-Electron-Microscope (SEM), Oeggerli produces black-and-white topographic images of each mite at the highest possible resolution, then painstakingly colors the b/w-scans based on realistic color data. Here, he captured an Eobrachychthonius sp., mite, which has been magnified 996 times.

For the microscopic analysis several specimens are mounted on special tape. Then, Oeggerli puts them inside the vacuum chamber of the SEM – in total darkness. Once everything is set, a beam of electrons scans the surface area of the sample. Pixel-by-pixel and line-by-line the machine detect electrons that are emitted from the sample during the analysis, eventually creating an extremely high-resolution, black-and-white topographic image (called SEM scan).

Oeggerli carefully selects angles that capture the unique characteristics of each mite, then applies realistic color to the images based on information obtained with an optical microscope. he uses color variation to enhance the unique structural qualities of the specimen.

Oeggerli applies realistic color to his images based on information obtained with an optical microscope, or sometimes from what can be just guessed with the naked eye.

The results are lifelike, fantastical, and awe-inspiring all at once. With his mite images, Oeggerli builds on the centuries-old traditions of Darwin and Dürer—blending science and art with modern technology, using his endless curiosity to inspire a new generation to explore the complexity and beauty of nature too small for us to see.

Are you interested to continue reading? Feel free to get a copy of Micronaut’s book ‹Micronavigating between Science + Art›.

About the book:

This book contains a selection of 70 fine works by scientific-photographer Martin Oeggerli aka Micronaut. The images reveal a surprisingly surreal microscopic life on planet earth. Accompanied with short descriptions, artist comments and introductory essay by Sibylle Sunda. 2nd Edition 2014.